What do you mean you can't adjust my bindings to my new boots? (Part 3: What is Backcountry Skiing?)

Backcountry Skiing looks cool- What is it and what do I need to start doing it?

There's evidence that skiing has been around since as early as 6300 BC. Most likely for moving quickly and carrying supplies efficiently across snowy terrain.

Skiing began out of necessity.

Since then, pleasure skiing has grown to approximately 370 million skier days per year. Who could've imagined that skiing would've grown into the multi-dimensional sport it has become?

In a previous post I mentioned different genres of skiing- Among those, I spoke of cross country and telemark skiing. I would consider those to be the forerunners to backcountry skiing.

Let's look at cross country first-

Skiing's most ancient roots resemble cross country (X/C) skiing.

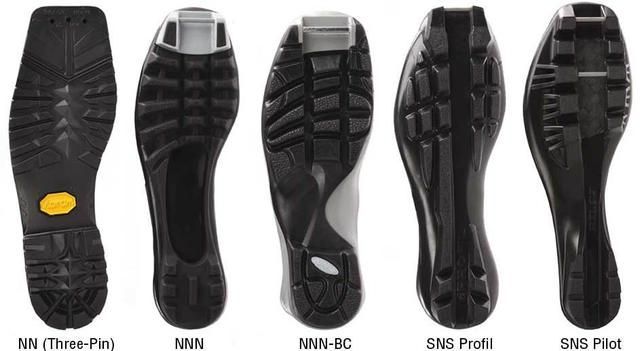

X/C skiing evolved to use long, skinny skis, wearing warm boots which resemble modern hiking boots. The boot originally attached to the skis with leather straps, then later, metal cables, and then more sophisticated bindings. X/C bindings, generally, do not release. The toe of the boot remains attached to the ski, and hinges while the heel lifts and sets down on the ski again.

Locomotion occurs in such a way that the hips, knees and ankles flex, in a motion similar to running. The weight bearing foot provides traction and propulsion, along with the poles (which are approximately armpit height). The other foot slides the ski forward, and the opposing arm pushes with the pole. Once the hips pass over the forefoot of the weight bearing foot, the heel lifts as the skier pushes off the forefoot, and weight transfers to the other ski. The unweighted foot glides the ski forward, and the cycle repeats with the opposite foot. For the most part, the motion is linear. Turning requires lifting the inside ski and moving it in the direction of the turn while pushing with the outside foot. The wider the step, the tighter the turn. Sometimes, animal skis were used to provide traction for moving uphill.

Modern cross-country skis remain long and skinny- they glide very well and allow for fast travel over snow. For climbing uphill, today’s cross-country skiers use different waxes and, in some cases, a base with directional textures underfoot (fish scales, etc.) vs. being smooth at the ends of the skis.

Some of them have a full or partial metal edge, and they’re a little wider- though, not much. Those so equipped are better for controlling the speed of descending pitches. However cross-country skis aren't a very stable platform for skiing downhill- especially for prolonged periods.

Their design, long and thin with deep camber, excels at propelling skiers forward across the tundra (essentially, groomed, flat trails).

Within the last century, the evolution of X/C gear has accelerated drastically. X/C gear has become quite efficient at moving people from place to place, quickly, over snowy ground, primarily having evolved into two styles (skate and kick), requiring different gear for each.

Below are photos of a cross country skier and gear. As you can see, the long skis, with a the heels free, would be quite awkward while descending a relatively steep slope at speeds much faster than one could propel themselves forward.

X/C Gear:

Telemark skiing is a similar concept. The Telemark style was born out of the necessity to move through the mountainous terrain of central Europe.

Modern telemark skis are wider, with a flat base and metal edge like alpine skis. In fact, many telemark skiers use a traditional alpine ski to telemark with. The wider, shorter, platform is better in descents than cross country skis, but that makes them travel more slowly over flat ground. Additionally, because the base is meant to glide better downhill, they don't travel uphill very well. So, telemark skiers attach climbing skins to their skis to make them able to travel uphill without the effort it takes to use techniques, like the herringbone, to go uphill.

The downside is that Telemark skiing has a long learning curve, and it takes a lot of strength and dedication to become accomplished.

Telemark skiing, undeniably, is hard work; it’s very demanding upon one’s balance, strength, and endurance.

Again, the boot is attached at the toe, and hinges such that the heel is free to move up and down.

The motion traversing flat ground, and climbing, is the same as X/C skiing. Descending a hill requires a body motion similar to doing lunges in the gym. It requires the skier to drop down in the lunge position, allowing one ski to trail the other, with the tip of the trailing ski, resting near the tail of the leading ski, creating a modified "C" shape over the length of both skis to affect turning. To change direction, you unweight by popping up out of the lunge position, slide the trailing ski forward and then rinse-repeat. It requires significant athleticism, where timing and strength are paramount. Three runs of telemark skiing on a groomed intermediate run are like doing ten runs (or more) on alpine skis.

The upside is that telemark skiers aren't tied to a lift all day long. With some understanding of the weather and snowpack, the only thing holding them back is how much endurance they have, and, if necessary, how much food and gear they can carry. They can go anywhere, anytime, if the snow cover is safe and they're skilled enough to handle the terrain.

All these things work together to satisfy the telemark skiers’ penchant for the backcountry.

In that regard, backcountry skiing is more about the expedition as a whole- a holistic approach, if you will.

Somewhere in Utah:

For east coast skiers, backcountry is decidedly different. The telemark movement is a small minority of overall skier numbers. In fact, they prefer their community to remain small- They enjoy getting away from people, specifically preferring to avoid. the droves of people who swarm ski areas on weekends. People are a turn-off to them, so they strive to find places people don't go to enjoy their sport. The social aspect of tele skiing isn't tied to ski houses because the lifestyle is more about healthy living and enjoying the comradery of a tighter knit, smaller fellowship.

Case in point- there has always been a group or two of hardcore telemark skiers at Killington who get together one or two days a week to ski lift serviced terrain, then, often, pack up and around to Cooper's Cabin for a meal and a couple beers. They've been known to pack up at night (or early morning) with headlamps- sometimes skinning up groomed trails to ski all around the mountain. Their entire lifestyle is based around healthy living, living within their means, being one with nature and their relatively tight community.

For the most part, the rest of the eastern skiing community skis traditional alpine equipment in-resort, with perhaps a small subset of them making an annual hike to Tuckerman's ravine in the spring, lugging their gear within and attached to backpacks.

Additionally, a small minority of skilled skiers may make the effort to boot pack to the top of Sugarloaf’s snowfields, or Castlerock at Sugarbush… even make the foray to Octopus’ Garden at Mad River Glen (which, of course, is NOT a ski trail -IYKYK 😉).

As far as actually living a lifestyle where a significant part of the day is spent touring to out of the way places to ski, that has yet to catch on as well as it has out west.

A quick blurb about Tuckerman’s Ravine:

Tuckerman's ravine is a bowl shaped feature on Mount Washington, New Hampshire- the highest mountain in the east. Mount Washington is known for its extreme weather, being greatly affected by the jet stream, having recorded the highest speed winds on the planet, at its peak.

Mount Washington is part of the Presidential range, a subset of the White Mountains, which are much older, geologically, than the Rockies, or the Himalayas, for that matter. At one time, that range was significantly higher, and grander- like the mountain range at the US continental divide, ranging as high as 15,000 feet at one time.

Over time, glaciation and weather eroded that range, leaving Mount Washington at its current peak of 6,288 feet. The ravine itself was formed by that same glacial erosion, during the Pleistocene Epoch, about 2 million years ago. Its natural shape (a glacial cirque- like an amphitheater) is excellent for holding snow into the spring, where with its varying pitches, moderately skilled and expert skiers alike, can enjoy a day of skiing and outdoor activities.

Tuck's is where the most (in)famous back country experience for New Englanders exists.

Tuckerman's Ravine (lower left- considered the birthplace of extreme skiing in the USA), The Raymond Cataract, (lower right) The Snowfields and Peak of Mount Washington:

Ease of access s a key element. Anyone who’s willing to make a not-so difficult hike to start their day, can access Tuckerman’s, without much specialty gear to get there. Once there, boot packing to the top of the trail you intend to ski is a workout, varying in difficulty with pitch. The steepest may require mountaineering equipment, like crampons and ice axes, but you don’t need to ski those runs to have a great day at Tuck’s. Mount Washington is, for the most part, open terrain with clear views of the mountain.

To access off-piste terrain at ski areas- most notably, at the infamous Mad River Glen, one would take a lift to the top, then make a relatively short traverse, through forest, over to the magical terrain that ski area is renowned for.

Few people outside the telemark community trekked outside of ski areas- and those who did found that it can be very difficult to map and manage the tree covered terrain. So, only the most hardcore skiers made ski touring a regular ski experience. Given its ease of access, Tuckerman's became a springtime destination, where most could boot pack, or easily snowshoe, the 3.8 miles from the trailhead.

Other genres of skiing spun off the idea of accessing back country terrain.

Over the years extreme skiing movies have glorified the thrill and excitement of skiing more extreme terrain, both inside and outside of lift service, along with the athleticism of performing tricks in that terrain. Hucking off rocks to land 40 feet, or more, from the take off point became old hat- so People began doing backflips, multiple revolution spins, landing switch, and continued to attempt more complicated stuff- all because people learned that such things were possible in the park- so why not do that in natural terrain too?

More and more people began searching out terrain beyond lift service, ducking ropes to ski outside defined ski areas. Thus, the idea of sidecountry skiing was born.

However, skiers soon discovered that there were reasons that terrain is not lift serviced; be it avalanche danger, difficulty of rescue, or just the risk associated with the more extreme terrain.

Stories of people dying in this "sidecountry" territory became more and more common in the news and in ski publications around the country.

In January 2000, a husband and wife- Greg and Loren Mackay- both experienced skiers; strong, healthy people (they owned a scuba diving business), dropped their child at day care, then ventured outside the gate at the top of 9990 (in the area formerly known as the Canyons- now part of Park City Ski Resort).

They never showed up to pick their child at the end of the day.

They perished in an avalanche, just outside the area boundary.

Once you leave an established set of trails, especially a ski area boundary, you are in the back country. There is no ski patrol, no frequent hikers, and no one to help you. You are on your own, and in real danger, no matter how experienced you are. In fact, you can easily get lost in-bounds, at many ski areas.

The message here is that proximity to civilization or a ski resort is meaningless. In that vein, don't kid yourselves- there is no sidecountry- everything outside of lift service is backcountry, and the proper precautions, along with knowledge of that kind of terrain and how to manage it. is the difference between life and death.

From that, an industry was born.

Still, you needed to access those places which lifts did not reach, to have those experiences.

Overall, the attraction to back country skiing is obvious. The beauty of the backcountry, tied to the allure of more extreme terrain and untracked snow, along with the appeal to multi-sport athletes, has come to define the sport.

But how to do this in the east?

Necessity is, of course, the mother of invention.

Over time an entire industry grew around backcountry skiing; avalanche training classes began popping up all over the Rockies.

With those classes, the list of gear grew quickly; specialty items like backpacks with inflatable airbags, sometimes costing $2,000 or more, ice axes, crampons for trekking on icy terrain, snow-saws, beepers, radio gear, packable shovels and probes to assist in finding and digging out people buried by avalanches, clothing layers specific for the better management of body temperature in back country conditions, and a host of other things became required for survival of a day of skiing.

For east coast skiers, that's a bit much for most of us to swallow. Mount Washington is one of the few places with avalanche risks, and the most accessible terrain existed at or near existing ski areas.

popularity of the sport.

the allure of backcountry skiing skiers continued to search out virgin terrain, claiming first turns on never-before skied slopes. Every year

Everyday working stiffs wanted access to big mountain, aggressive skiing, without the costs of helicopters, snowcats, and the budget a film production team provides.

Yet, that terrain remains close, and available, existing as territory outside the lift service of ski areas. Much of it is a short hike away from the lifts.

So, your heels attached. There are obvious issues, not the least of which are trying to land a 40 ft jump with out a solid landing platform.

"Ok dude, enough- get to the point about my boots now working with my bindings.:

Here are some AT binding examples:

Some of the differences are obvious- The top binding requires special slots in the heels of your boots to hold your boots down for using them like a traditional binding.

If you go back to the first picture in this post with the orange Scarpa boot, you can see that the heel piece of the binding does not clamp down over the boot's heel lug, like this one. Once you step down, you're locked in. It's not really meant to release (it will, but not easily).

standardThe advantage is that it's very light. If you spend the majority of your time touring, as opposed to downhilling, this rig makes sense.

The binding in the lower photo allows you to use a more traditional boot to binding interface, but the boot still needs to have some way to hinge freely at the ankle. It's a heavier rig, and the thought is that it allows an easy transition to back country skiing, and that you can use a heavier (tougher) boot. Touring boots, while much lighter, they're a bit more flimsy, and not as stiff.

Anyway, you defintiely can't use traditional alpine ski boost in the top photo, at least, without having the proper inserts installed. But that doesn't solve how the boot will flex freely at the ankle.

It's also not recommended for the one in the lower photo. You'd have a much lower range of motion and your foot is more likely to slip in the boot, creating excessive wear, blisters, and worse.

So, referring back to part 1 (The GripWalk thing), there are standards.

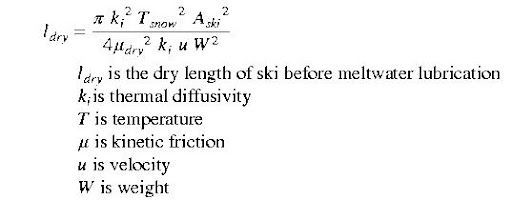

The different standards and boot sole shapes (ISO 5355 for alpine, ISO 9523 for touring, ISO 23223 for GripWalk) mean that it's crucial to verify boot and binding compatibility, and AT bindings are not universally compatible with all boot standards.

Additionally, ISO 13992 ski boots may LOOK like they';; work in traditional alpine bindings, and you may be able to click into them, the toe and heel lug shapes Do not conform to the ISO 9462 standard for alpine bindings, and they don't hold or release properly. Additionally, they don't have a flat anti-friction surface at the bottom to interface with the AFD on the binding:

So, there you have it.

Some vendors think it's ok to use the ISO 13992 boots with alpine bindings, and will try to sell them to you under those auspices.

This happens because the standards can be confusing, allong with the labelling on the boxes and the descriptions on the product websites.

Know your products and their compatibility- especially if you're buying something you can't return.

That's it for this topic...

For now, at least.

Good luck!